| X Bienal de Nicaragua by Abraham Cruzvillegas (source) - an exhibition exploring the relationship between individuals and their environment |

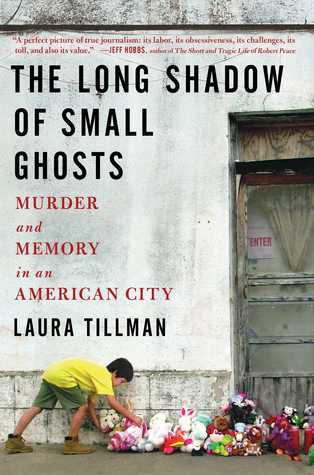

John Allen Rubio, the father of the children, has issues: an abusive childhood home, low IQ, extensive drug use, poverty, and mental illness (including what appears to be schizophrenia). He says he killed his children because they were possessed, which he had confirmed when he performed a folk-healing ceremony.

Author Laura Tillman spends much of the book expatiate about how to decide if someone deserves to be killed for their crime, if we should judge psychotic-John-at-the-time-of-the-murders or a competent John who had emerged from his psychotic episode. Although this type of mulling and re-visiting thoughts trying to understand your own position on the death penalty might interest some readers, I have to say that at many points in the book it was very clear that Tillman lacks a guiding compass that Brian Stevenson (author of Just Mercy) uses to make everyday decisions about his life, work, and spirituality.

The persistent wondering about questions of life, death, mercy, and justice without seeking input from any of the world’s recognized philosophers, deities, or spiritual guides bothered me because it came across as a very American idea of naively going on a one-woman journey to find profound answers that one will be able to uncover within oneself. As in, the conclusions that Tillman reaches through talking to neighbors, visiting the haunted apartment where the murders happened, writing about her feelings, being skeptically curious about Mexican witchcraft/folk-healing, etc, will guide her to a place where she will decide for herself, based on her emotions, if she thinks someone deserves to die: “I, and you reading this, we are compelled to decide if we want to kill John. I need to look him in the face.”

I believe that only God has the right to decide if, when, and how someone dies. The whole argument of “Was John crazy or not at the time of the murders, and thus deserving of capital punishment or not?” becomes immediately irrelevant if you don’t believe in capital punishment. John could be the most cruel and calculating sociopath ever, he could have done far worse than stabbing his kids, and I still would say that he gets to die when God decides.

| X Bienal de Nicaragua by Abraham Cruzvillegas (source) |

“To kill another person exists on another plane from the act of dismantling bricks and wood beams. The parallel is found in the satisfaction promised by destruction: to lend the weight of tangibility to the ephemeral. You can take a mallet and bust into the wall of a building. You can load poison into a syringe and inject it into the body of a human being. You can see them both reduced to absence. Then, we are left with nonexistence, a blank space. A piece of earth can host another structure, and though it will be different than what came before, it can serve a new purpose. But when a life is gone, it is not replaced.”

The various times that Tillman brings up the role of architecture and place in shaping history and communities is where she really shines. What relationship did the claustrophobic, windowless apartment have in provoking Rubio’s madness? And what effect does the knowledge of the existence of a still bloodstained room have on the neighbors? Like much of the book, these questions have less tangible answers, but they remain fascinating to me.